Building on the results of an internal workshop looking at different methods for engaging with communities, we have elaborated a set of six principles to help us enhance community engagement in profiling processes. These are currently being applied in the ongoing exercises in Greece, Sudan and Honduras.

This article is part of our series on community engagement in profiling, which looks at both specific country contexts (such as Greece, Sudan, and Honduras) and our efforts to improve our practices overall.

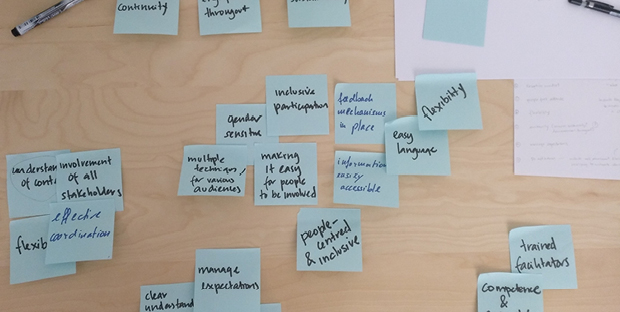

JIPS-internal workshop on community engagement principles.

As highlighted by Cecilia Jiménez-Damary, Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons, in her note on the “Rights of internally displaced persons”, inadequacies and inconsistency on community engagement can lead to poor consideration of affected communities’ needs and perceptions and thus inadequate solutions.

Engaging with displacement-affected populations throughout a profiling process not only helps us improve the depth and quality of the evidence-base. It can also empower affected populations by supporting them in taking an active role in the production and validation of data based on their own priorities and realities, while at the same time ensuring access to the information they need to make informed decisions about their situations.

At JIPS, we have made community engagement one of the main concerns in our 2018-2020 strategy as well as part of our work on durable solutions, and have engaged in an internal reflection on when and how along the profiling process to concretely work with communities.

Internal workshops, research, and discussions with partner organisations helped us to identify six main principles on community engagement in profiling, which we are now concretely implementing in the field.

These principles are intended to guide different actors involved in a profiling exercise (whether governmental authorities, UN agencies or other humanitarian and development actors) on how to better engage affected communities and make sure their needs and perceptions are taken into account. Here are our six principles:

1. Accountability and transparency

It is important that communities clearly understand why a profiling exercise is taking place, what type of data will be collected, how it is expected to be used, and who is involved in the process. This implies dealing transparently with expectations and spending time building and sustaining trust throughout the data collection process, as well as fostering respect between communities, authorities and other partners involved.

2. Conflict sensitivity and do no harm

Community engagement in profiling exercises needs to be sensitive to any impact of the process on the populations that is trying to engage. This requires consideration of potential root causes of displacement, the cultural and societal nuances of the context, community dynamics, and any protection risks. A careful ethical consideration is needed to balance the risks and benefits that may be related to the data collection, analysis and dissemination, including putting into place the necessary data sharing protocols.

3. People-centred and inclusive

Community engagement in profiling exercises needs to be sensitive to differences arising from diversity in the population, and ensure the inclusion of marginalised or difficult-to-reach groups. This may require tailoring tools, communication channels, feedback mechanisms and strategies to reach diverse audiences.

4. Professionalism and rigour

Engaging with communities requires specific skills including facilitation and conflict resolution, as well as adequate mechanisms to capture, process, share and disseminate the data collected. Partners involved need to account for these skills and competencies and undergo appropriate training when needed.

5. Engaging in context

Prior understanding of the social, political, and cultural context is required for accessing and engaging different groups appropriately. This is relevant for both planning and implementing phases, and may include analysing local dynamics, power relations, protection risks, how different population groups are organised as well as how they interact with relevant local stakeholders, organisations and institutions.

6. Continuous learning

Community engagement requires careful planning, but also adequate monitoring and evaluation to encourage working in this way more broadly, disseminating good practice, inflicting no harm and promoting a better quality of the data. This implies establishing mechanisms to systematically capture lessons and incorporating them into relevant guidance and training materials.

Lively discussions at the JIPS team workshop to define our key principles for community engagement.

Building on our long experience involving communities at different stages in the profiling process (see e.g. how we used video in Sittwe, Myanmar, and hear more in future articles to this series), we are currently working to advance our practices. For this purpose, we are engaging with communities in different ways, e.g. as part of our work on durable solutions for IDPs but also in the following three field projects:

Affected communities were involved from the beginning of the profiling exercise, launched in August 2017. For instance, focus group discussions were held alongside the development of the analytical framework for the exercise. This helped tailoring the methodology to the specific context and ensuring that the affected populations’ perceptions and priorities were taken into account in the development of programs and solutions.

During focus group discussions with refugees, asylum seekers and documented and undocumented migrants, we used visual and ranking methods (sticky notes and wallpaper) to better understand their future intentions, the factors that might influence these intentions, as well as women’s and men’s perceptions of their local integration.

Communities are being involved in this profiling exercise at different stages, including data collection, validation, and formulation of the baseline information. Participatory planning techniques and mapping approaches are being used to involve displaced and host communities, and better understand communities’ perspective and priorities, for instance, with regards to preferred durable solutions or priority areas of intervention.

Results from these community engagement exercises are shared with local authorities and other relevant actors, to inform their durable solutions and urban planning approaches.

A protection-sensitive and context-specific qualitative methodology was adopted to help us better understand how neighbourhoods are affected by criminal violence and the prevention measures that can better respond to the realities in their communities. Unlike previous examples, and due to the sensitivity of the context, the approach adopted was one-way communication, more focused on gathering information.

Focus group discussions (FGDs) were tailored and designed together with local partners (such as World Vision Honduras) and experts in protection and displacement caused by criminal violence. Questions were tailored to capture gender-specific data, and allowed to disaggregate the data by age and sex.

Once the first lessons are captured from the pilots, the team will further discuss the principles and endorse a final version in an upcoming workshop in May. In parallel, the engagement with affected populations will be further mainstreamed into the profiling process through the adaptation of existing tools and guidance in the JET. Where necessary, new guidance and tools will be developed.

Moreover, the team continues to meet and discuss with relevant partners to share lessons and experiences on engaging with affected populations and ensure a collaborative inter-agency approach to community engagement and data cycle. Lastly, our colleague Isis Nunez Ferrera is taking part in this year’s UNHCR Innovation Fellowship to further pilot ways of community engagement in profiling.

Stay tuned to hear more from this series, including on how community engagement can be shaped in urban contexts and how it can be implemented as part of a comprehensive durable solutions analysis!