Work implemented in 2020-2021 by JIPS together with UN-Habitat and the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) highlighted the critical need for a paradigm shift in addressing forced displacement in cities and towns. These efforts largely fed into the report of the UN High-Level Panel on Internal Displacement (UN-HLP) and the subsequent UN Secretary-General’s Action Agenda, which recognize that internal displacement is an increasingly urban phenomenon and should thus be addressed as part of urban planning.

Importantly, cities should not be seen as only the backdrop where displacement occurs, but as a rich ecosystem that can contribute to the resolution of displacement. The strategic need for urban profiling is specifically highlighted to inform a shared understanding of capacities and vulnerabilities of displacement-affected communities as well as the urban ecosystem to better inform responses.

“The momentum created by collaborative urban profiling, when harnessed, can lead to enhanced local institutional leadership.”

This research publication puts the spotlight on the use of urban profiling, and on the pathways that link it to global priorities for urban displacement response. The analysis combines a desk review with semi-structured key informant interviews to put the views of local authority representatives and development practitioners front and centre. It draws on profiling exercises that JIPS has supported in Iraq, Somalia, Syria, Yemen and Ukraine. The findings from can shape a more impactful design and implementation of urban profiling, and enhance the practice of local and international actors working on analysis of displacement and response in cities.

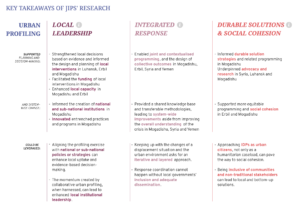

Local government officials and urban practitioners involved in this research saw a direct relationship between the collaborative nature of the profiling process and the use of its results, with its contribution going primarily into informing planning and decision making. In some cases, urban profiling even motivated system-wide changes by highlighting institutional gaps and by providing a basis for addressing social cohesion.

Overall, this research revealed that urban profiling is much more than the sum of its parts and analytical approaches. There are numerous positive externalities of collaborative processes, such as the embedded capacity building or capacity sharing. But it was also the tailored analytical approaches to stakeholder information needs and context constraints that helped urban profiling support a better response . The below visual summarizes how the analytical components of urban profiling have supported the different global-level priorities:

Moving forward, expanding the research to other urban profiling exercises and displacement settings would allow further testing the relations uncovered by this study, for more generalisable findings. This could also explore how the inclusion of IDPs and non-traditional stakeholders can be strengthened; how the findings can be disseminated more effectively and broadly among the diverse stakeholders involved in responding to displacement in urban settings; how applying an iterative and layered approach to urban profiling can be used to enhance the analysis and keep the data updated and useful over time; and how to better embed the profiling exercise in, or align it with, national and sub-national planning and budgeting cycles, particularly in contexts with ongoing humanitarian interventions and thus diverse information needs.